An AI look at the concept of ikigai in the new year, courtesy of Stable Diffusion

tl;dr: As the year comes to a close, many of us reflect on finding more purpose and meaning. The popular ikigai Venn diagram promises a formula: find the overlap between what you love, what you’re good at, what the world needs and what you can get paid for.

But this myth misses the mark on the original Japanese concept. Rather than a destination, ikigai is a journey. It’s about starting small, releasing yourself, seeking harmony, appreciating little joys and being present. I present Mogi’s framework as a way to help identify and sharpen focus on the everyday meaning as we enter the new year.

I hope that Mogi’s insights will help you explore a wider spectrum of life’s diverse joys and purposes. Challenge the assumptions and assertions that purpose is an intersection of concepts on a page. Instead, discover ikigai through living life more fully.

Ikigai

You may’ve seen a popular take on ikigai in a popular and often used Venn diagram widely shared on social media (such as here and here) and in self-help books, depicting it as the intersection of four circles: what you love, what you’re good at, what the world needs, and what you can be paid for.

But as Nicholas Kemp shared in his article “Ikigai Misunderstood and the Origin of the Ikigai Venn Diagram”, this popularized view isn’t an accurate representation of the Japanese concept of ikigai. Rather, it’s a Western invention that oversimplifies and distorts the original meaning of ikigai.

“Full credit for the Venn diagram of Purpose should go to Spanish author and psychological astrologer, Andres Zuzunaga, who created it in 2011. It first publicly appeared in the book Qué Harías Si No Tuvieras Miedo (What Would You Do If You Weren’t Afraid?) by Borja Vilaseca in 2012. Eventually, the diagram was translated into English and then started being used by HR managers and life coaches as a simplistic overview to finding purpose in your career. It is now used to help people create a more balanced work situation.”

Ikigai history

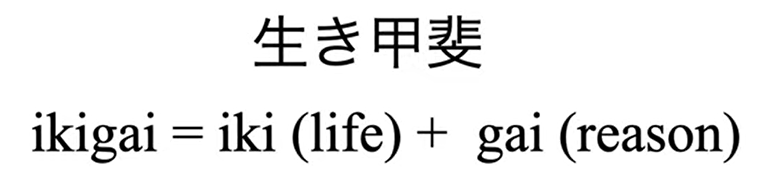

A little history. Based on what I’ve read about and discussed ikigai throughout my career, Ikigai is Japanese for “life” (iki) and “reason” (gai), which roughly translates to “a reason for living (or being).”

I subscribe to Ken Mogi’s outline that the real ikigai is not a formula for finding your purpose. It’s a way of living that embraces the joy of being alive. Japanese people don’t use this diagram, nor do they ask themselves the four questions that it suggests. They just follow their ikigai.

It’s not a goal, destination, or something you find, but rather a journey, or something you feel and experience. It’s dynamic and can be highly personal and diverse. And ikigai isn’t limited to your work or the path of career but includes all aspects of your life: just scratching the surface, it’s your relationships, your passions, your hobbies, your values, and even your dreams.

Pillars of ikigai

In his book, The Little Book of Ikigai, Mogi introduces five pillars of ikigai that provide a supportive framework and can help you awaken and cultivate your ikigai in everyday life:

- Starting small: focusing on the details and appreciating the small things that make you happy.

- Releasing yourself: accepting who you are and expressing your true self without fear or judgment.

- Harmony and sustainability: relying on others and contributing to the common good.

- The joy of little things: enjoying sensory pleasures and being present in the moment.

- Being in the here and now: finding your flow and immersing yourself in what you do.

Rather than hard and fast prescribed rules, Mogi’s pillars are guidelines and suggestions, intended to be provocative and complementary, while flexible enough to be used creatively and experimentally. They are not based on scientific evidence or empirical data, but on cultural wisdom and personal stories. Mogi writes…

“They are not mutually exclusive or exhaustive, nor do they have a particular order or hierarchy. But they are vital to our understanding of ikigai, and will provide guidance as you digest what you read [in his book] and reflect on your own life. Each time they will come back to you with a renewed and deepened sense of significance.”

Representing ikigai

The four-circle diagram of ikigai above may be appealing and convenient, but it’s misleading and incomplete. It reduces ikigai to a formula that can be applied to anyone and anything, but ignores the complexity and diversity of human life. It implies that ikigai is a rare and elusive phenomenon, but it neglects the abundance and accessibility of ikigai. And it suggests that ikigai is a product of optimization and maximization, overlooking the importance of exploration and experimentation.

Ikigai is much more than the popularized diagram and the chance intersection of four key mystical ingredients: it’s a spectrum that reflects the richness and variety of what makes life worth living, and a growth mindset that enables you to embrace and enjoy the challenges and opportunities that life offers. Mogi offers that what you’re good at, what you love, what you can be, what the world needs… these can all be your ikigai:

“It’s all the diversity… the whole spectrum is what’s so important. The whole area [in the popular Venn diagram] should be your ikigai.”

He goes on to suggest that there are four categories to consider in a true ikigai diagram: Small, Big, Public and Private. I represent these in the following way, adding some structure to his white board outline:

“In your life, there are small joys and big joys and purposes, and also there are private and public joys and purposes: ikigai is all of these things. The idea of ikigai is very democratic… a whole spectrum of the diversity of things that gives your life some deeply rooted joy… all of this is ikgai.”

Quite simply, ikigai is a philosophy that can inspire you to live authentically and meaningfully. It doesn’t depend on external forces and material things – recognition, fame, or wealth – but on internal and deeply personal ones, such as fulfillment, joy, satisfaction. It comes about and is developed through your own intuitive discovery rather than methodical and rational calculations: more emotion than a matter of logic.

Ikigai isn’t something you find through a chance intersection of components outlined in a blog post: it’s something you do.

Please let me know what ikigai means to you. Is it something to find, or a way to experience life more fully?